This is the final part of our three-part series on how eSIMs can support mobility, connectivity, and contingency in field settings.

eSIMs are not just convenient. They are already essential tools for maintaining communications in insecure, disrupted or cross-border environments. For many field personnel, they have long been part of a wider digital toolkit used for maintaining connectivity and reducing downtime.

But they are not without risks.

In this final part of the series, we unpack some of the technical and operational concerns that come with eSIM use, especially in sensitive locations. We also touch on organisational responsibility, the realities of digital exposure, and where good practice in the field still needs to catch up.

Start with Practice, Not Just Possession

As highlighted in Part 2, having a tool and knowing how to use it are two different things. It is easy to download an eSIM profile. What is harder is understanding how and when to activate it, how it behaves under different coverage conditions, and what your fallback is if it fails.

We regularly hear from experienced professionals who get caught out in their first week with a new eSIM. That moment when the app is asking for a verification code via SMS, but your primary SIM is already offline. Or the moment you realise you are on roaming, but your WhatsApp or Signal messages are not sending, because the background data settings were restricted.

These are not high-tech issues. They are basic use issues. Which is exactly why they matter.

Signal Exposure and Surveillance: The Bigger Picture

Many people assume an eSIM makes them more secure because it is digital. This is a misunderstanding.

The risks from mobile tracking do not come from the plastic SIM card itself. They come from the interaction between your phone, the network, and the apps on your device.

For example:

- Signal triangulation: Your position can be estimated using the strength of your signal to multiple towers. This is a basic function of how mobile phones work.

- Subscriber data exposure: When your phone connects to a network, it shares a unique subscriber ID called an IMSI (International Mobile Subscriber Identity) and a device identifier known as an IMEI (International Mobile Equipment Identity).

- Background app behaviour: Many apps quietly send or request location data in the background, especially maps, browsers, and health or fitness tools.

- Automatic connections: If Wi-Fi or Bluetooth are left on, your phone may attempt to connect to nearby networks or devices without prompting.

These behaviours continue whether you use a physical SIM or an eSIM. They are part of the mobile ecosystem.

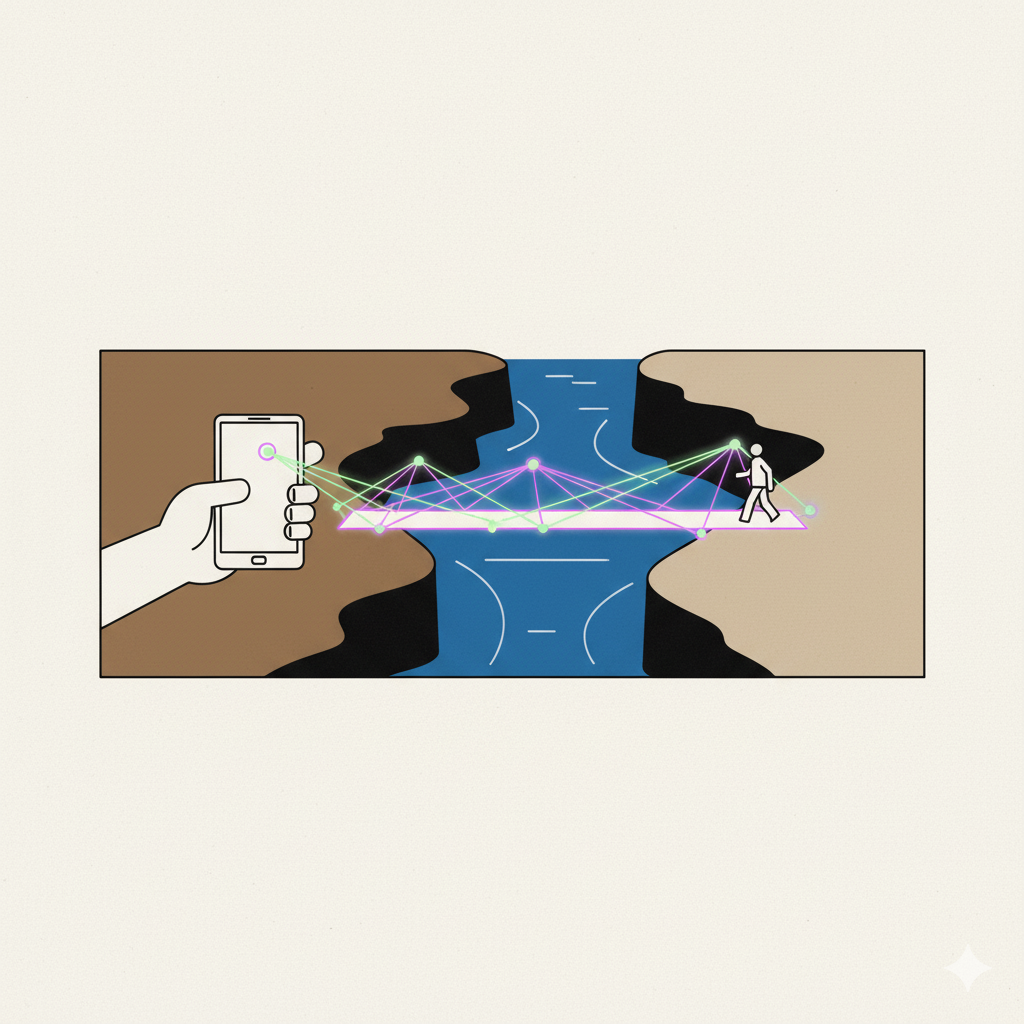

Use Case: Proximity to Borders

Let’s say you are near a national border or line of control. Your local SIM stops working. However, from certain hills, buildings or vehicles, you may be able to reach the signal of a neighbouring country.

eSIMs can allow you to preload profiles from multiple countries. This means you can switch without having to change hardware. This also allows you to maintain data connectivity when moving across borders, or when operating in areas where local telecoms infrastructure is patchy or unreliable.

In some field scenarios, teams have placed static receivers in elevated locations to improve reception. Others have learned where to walk or drive to gain signal from the neighbouring network.

These workarounds only matter when someone has taken the time to prepare them.

Individual Tools, Shared Responsibility

It is no use being the one person in the car who switches off your hotspot and masks your traffic if your colleague next to you is running open Wi-Fi with a dated messaging app.

Many of the behaviours that reduce digital exposure require consistency across a team or organisation. This includes:

- Turning off automatic syncing and location sharing when not needed

- Using encrypted messaging apps with disappearing messages

- Understanding how and when to switch between data sources

- Not relying solely on one device or network

- Charging in safe, trusted sources and having backup power

Equally, responsibility does not stop with the user. We know some organisations still do not make VPNs available. We suspect the same is true for eSIMs. These are small investments that reduce friction, increase safety, and make teams less reliant on hotel Wi-Fi, roaming, or untrusted local SIM vendors.

The Data We Hold

It is not just your own privacy at stake. Those of us in field-facing work often hold sensitive contact lists, chat histories, media files and programme documents. These may include information about colleagues, beneficiaries or partners.

All of this can be at risk if your device is compromised. That risk increases when devices are shared, when apps remain logged in, or when verification messages are routed through vulnerable channels.

Even if your apps are locked down, the metadata your phone shares can still be used to profile your movements and interactions. This includes:

- Which towers you connect to

- When you connect or disconnect

- Who you send messages to and receive messages from

- What services you use and when

eSIMs Are a Tool, Not a Guarantee

An eSIM gives you more options. That is its main value. It can be used as a backup or as a primary data source. It can be installed on tablets or phones. It can allow your device to jump between networks without fiddling with SIM trays in a dimly lit airport or car.

But it is not a guarantee.

If the network is cut, or if the eSIM app fails, you still need backup methods. That may include satellite messengers, radio contact, or simply a printed comms plan shared with others.

We recommend every team maintain at least one secondary device with a separate provider, one portable power source, and a clear set of comms practices for each location.

And we always recommend that data downloaded through an eSIM be run through a secure VPN.

Final Thought

There is no perfect tool for field communication. But eSIMs, used with care and understanding, offer real advantages. They are already in use. They are not the future. They are now.

This article is the final part of our three-part series on eSIMs in operational and high-risk environments. If you found this useful, please consider sharing it with others in your network. We also welcome your feedback, use cases and insights in the comments.

You can revisit the earlier articles here:

And if you would like help boosting reception at your field site or choosing the right tools for your team, get in touch.

Want help setting up or boosting eSIM performance? We’ve supported field teams with eSIM configuration, signal boosting, and fallback planning. If you’d like a second pair of eyes on your setup, feel free to get in touch.